Uber has quietly changed the way it pays drivers in several major cities across the U.S., using a new feature it’s calling “Upfront Fares.” Instead of paying drivers for trips based on just time and distance, it’s now using an algorithm “based on several factors” to calculate the fare. What all of those factors are is unclear. Uber has long used an upfront pricing algorithm to determine how much passengers pay, which is one of the reasons riders sometimes see vast price fluctuations.

The company says the new feature provides drivers with more transparency. They see more details of a prospective ride before accepting it, such as the fare and pick-up and drop-off locations, which is something drivers say they’ve been asking for. In the past, most drivers wouldn’t receive this information until after they accepted a ride.

Uber spokesperson Harry Hartfield said upfront fares are about giving drivers “more control and choice” but will include a “balancing” of payments. That means, he said, drivers will make less money for longer trips but should earn more on shorter trips.

Some drivers say, however, that they’ve mostly seen lower earnings overall since the change. On top of that, they say, it seems like Uber is taking a bigger cut of fares.

There’s no rhyme or reason to it.

Sam Vance, UberX driver

“Before, you could guestimate—back of envelope calculate—and see that [the trip is] this far and this long and figure out you’ll make this much,” said Sam Vance, who’s been a full-time UberX and Lyft driver in Columbus, Ohio, for more than four years. Now, “it’s not based on anything. There’s no rhyme or reason to it.”

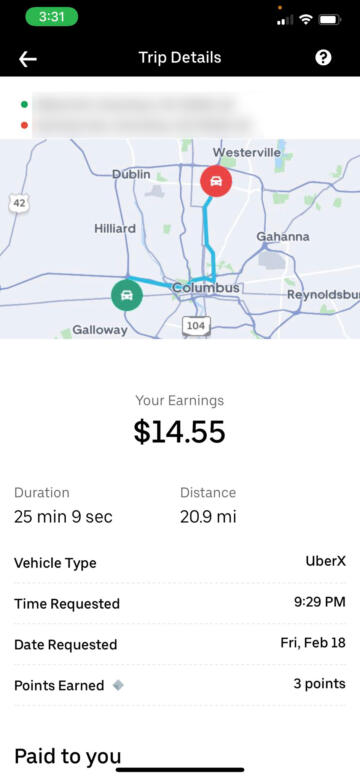

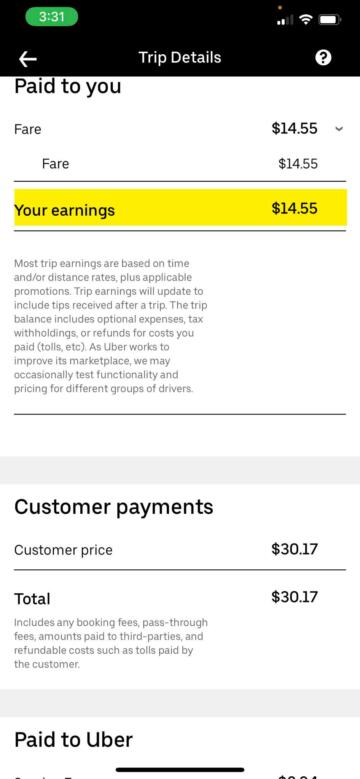

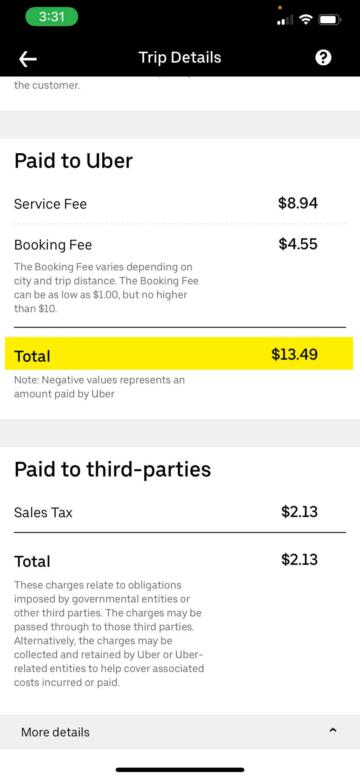

Uber has long said the average amount it takes from fares is about 25 percent. But Vance shared screenshots with The Markup of two recent trips he did for Uber that show the company took far more. One shows a customer paid $30 for a 20.9-mile trip, Vance earned $14, Uber got $13, and the rest went to sales tax. The other trip, which was 8.8 miles and included an airport drop, the customer paid $22, Vance got $6, Uber took $9, and the remainder went to airport fees and sales tax.

When asked about its take from Vance’s trips, Uber’s Hartfield said these trips were not necessarily representative of Uber’s usual take. Vance said that Uber often takes around half the fare.

Before Uber’s change in pay structure, Vance said he’d normally average around $1 per mile once time and distance were calculated, especially if he was driving on the highway. So, the 20.9-mile trip would have earned him about $21, and the 8.8-mile trip would have brought in roughly $9.

“Some drivers are really looking forward to this because they think it’s going to be a positive change,” Vance said. “But it’s not what you think it is.”

The Rideshare Guy blog (which partners with Uber and receives commissions for signing up new drivers for the company) was the first publication to detail Uber’s new pay structure. Reuters additionally reported on it last week. According to both sources, Uber has rolled out upfront fares to a total of 24 U.S. cities in states including Texas, Florida, and throughout the Midwest. It appears the company initially started testing the pay structure in a handful of cities about six months ago, including Columbus, where Vance lives.

“Black Box Algorithms”

Uber isn’t the first gig company to experiment with algorithms to calculate driver earnings. A few years ago, Instacart, DoorDash, and Shipt started calculating pay for their delivery couriers using what workers call “black box algorithms.” Anecdotally, many couriers for those delivery companies have said the seemingly arbitrary fluctuations of the pay algorithms have made it harder to predict and figure out their earnings. They also say they’ve seen their pay decline over time.

Worker advocates say using concrete factors, like time and mileage, helps drivers and couriers better assess if a trip is worth taking and understand how they’re being compensated.

The more opaque the fare calculations, the more drivers, regulators, and the public have a hard time holding the gig companies accountable to fair and transparent pay standards, said Amos Toh, a senior researcher for Human Rights Watch who studies the effects of artificial intelligence and algorithms on gig work.

“Uber didn’t come out and say this is going to be algorithmic, but the criteria that they are using—a range of factors and things that aren’t specified—could indicate that the fares are going to disappear behind a black box algorithm,” Toh said. “When you put a fare calculation behind a black box algorithm, it’s possible to have the capacity to learn from driver behavior … and actually learn what is the lowest rate a driver will take for a ride.”

“We don’t have any evidence that Uber is doing this,” Toh added. “But the real problem is the secrecy, because it makes it impossible to verify.”

Uber’s Hartfield didn’t respond to questions about why Uber changed its pay structure in these markets, when the pilot first began, or whether it plans to take it nationwide. He also didn’t respond to questions about what cities currently have upfront fares or how Uber’s algorithm calculates driver fares.

[T]he real problem is the secrecy, because it makes it impossible to verify.

Amos Toh, Human Rights Watch

When asked for all of the factors that are taken into account to calculate drivers’ fares, Hartfield said in an emailed statement, “Rather than just the time and distance of the trip, upfront fares are based on a much more comprehensive set of factors including base fares, estimated trip length and duration, real-time demand at the destination, and surge pricing. While earnings are subject to seasonal demand patterns and the types of trips a driver chooses to take, we haven’t observed an earnings impact due to this pilot in cities that have had upfront fares for more than six months.” He didn’t respond to questions about whether this was the complete list of factors or whether there were more factors.

Hartfield said The Markup could “learn more about the pilot” from the blog post by The Rideshare Guy and also sent a link to a YouTube video by Uber about upfront fares, saying, “It’s worth looking through the comments under the video, most of which are from drivers saying they’d like to see these changes in more markets.”

The video has several comments from drivers saying they’re happy to see more trip information before accepting a fare. Other commenters say they don’t like the idea of being paid less for longer rides. Several Reddit threads and comments on driver forums have also popped up, with drivers who’ve tested the feature saying they’ve often seen lower fares, confusing fare drops during rides, and an overall decrease in rides.

Along with upfront fares, Uber has also rolled out a companion feature in those 24 cities called “Trip Radar.” The way it works is that Uber shows a trip to several drivers at once, and whoever accepts the ride first gets it. Vance said he usually only has a second or two to see it and click, so he doesn’t have time to see the upfront details right away.

“It’s kind of a moot point because it comes up so fast on the screen, and there are four or five other drivers tapping on it,” Vance said. “It’s like Hungry Hungry Hippos, and everyone is tapping.”

Hartfield didn’t respond to request for comment on drivers not having time to see upfront details with Trip Radar and having to compete for rides.

Vance said recently, in his haste to accept a ride, he got stuck on a five-hour round-trip drive to Cleveland. For that trip, he earned just $90. Before Uber instituted upfront fares, Vance said he liked doing longer trips. Back then, he said, a trip to Cleveland would usually net him at least $140.

“Because there’s no longer a rate card, that’s interrupted the way drivers drive. Your strategy just has to be different,” Vance said. “Now you have to stay out longer, and it takes a lot more to make money, and you don’t make as much.”